by Luanjiao Aggie Hu

Part 1 of 2

Last year, I became a mother when I gave birth to my first child on his due date. Before this, I had many other identities: new immigrant on a U.S. work visa, physically disabled woman using a prosthetic leg, Chinese/Asian person, disability researcher, and advocate. After having my child, being a mother was added to these identities, triggering unexpected interactions in my life experience.

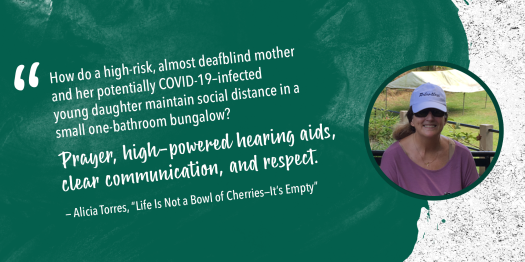

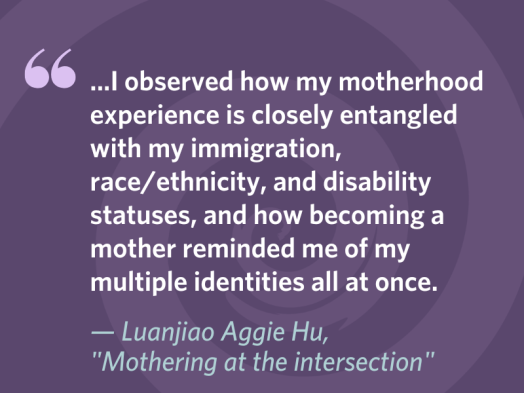

Feeling like a mother was a gradual process for me, an identity that grows on me as my son gets bigger. The feeling of becoming a mother has been enhanced by everyday childcaring tasks: changing diapers; feeding, entertaining, bathing, putting my child to sleep; comforting my child when he is ill or upset, etc. Meanwhile, I observed how my motherhood experience is closely entangled with my immigration, race/ethnicity, and disability statuses, and how becoming a mother reminded me of my multiple identities all at once. This reminder started with the childbirth experience and was intensified as I struggled with childcare tasks.

It was unfortunate that my labor experience at the hospital was disempowering and traumatic, which directly led to a long and challenging postpartum recovery.

I do not believe I received adequate support from the medical team at the hospital. I gave birth on Labor Day, a national holiday. It was possible that the hospital was understaffed at that time and due to the summer peak in childbirths. In the delivery room, the communication between me and the medical staff was frustrating, and I obviously felt that there was some kind of barrier. Significant communication between us was futile and attempts did not lead anywhere. This may be a problem not of the language itself, but of a deeper difference in culture and thinking—or there may be other factors involved.

The medical staff and I could not understand each other’s intentions well. At one point, I asked to wear my prosthetic leg to help with the childbirth, and my request was rejected by the doctor on duty. “It would not make any difference,” the doctor said. I had not met or interacted with this doctor in my previous prenatal appointments. The midwife on duty, whom I had met once in my prenatal appointments, commented to me in the delivery room, “The sooner this ends, the better it is for everyone.”

This comment, among other disempowering details, became the last straw that crushed me. The comment left me with the realization that the medical team wanted me to take the advice to go for a C-section sooner and stop wasting everyone’s time. There was some but not enough progress in the hours-long delivery attempt. I tried to give birth intermittently and also had to spend energy advocating for myself and asking for help; finally, I was exhausted physically and mentally. My fighting spirit was crushed, and I felt utterly vulnerable with an epidural on and my prosthetic leg off. Although my full-term baby showed no signs of distress in the womb, I was advised and eventually had to agree to go into the operating room to have a cesarean section. My baby was neither in an unfit position nor large in size (7 lb 3 oz).

In other words, I spent more than six hours in the delivery room trying to give birth on and off before being sent for a C-section. During the six hours of pushing, there was significant waiting time for the doctor and midwife and difficulties communicating with medical staff as I tried to advocate for myself and ask for help, even as I would eat a bit of jelly and then vomit due to the influence of the epidural. On my child’s due date, my mood changed from excitement and anticipation to anxiety and impatience, and finally to extreme disappointment and despair in the hospital. To this day, writing this experience down brings tears and profound sadness to me.

Such racial/ethnic differences in cesarean delivery rates have persisted over time and engender justified concern about the potential overuse of cesarean delivery in certain race/ethnic groups. Another study points out that perceptions of physicians and healthcare providers in the U.S. toward patients with disabilities are concerning and this could potentially have an adverse impact on the quality of healthcare received by people with disabilities. As an Asian woman with a visible physical disability, my experience in the hospital becomes one of the stories attesting to these findings.

It’s hard to recall what happened in the delivery room, a wound that still feels fresh. I remember many things and recounted the difficult process to my partner in the hospital. It was a draining task during our first days as exhausted parents in the maternity ward. I recorded our conversation, as I was ambitious and wanted to see if there were legal grounds to pursue this matter since I did not believe that the medical team provided me with sufficient support. I eventually dropped the idea because taking on a motherly role has been so challenging and all-consuming. When I shared my experience with my family in China, I learned how my two sisters had similar experiences in their labors yet more positive outcomes due to different guidance and medical support. Both my sisters have had natural births in Chinese hospitals.

In Part 2, Aggie will describe her experience as a new mother with a disability.

Luanjiao Aggie Hu is a postdoctoral fellow at the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy.

Access Aggie’s Tedx Talk, “What Does Freedom Mean to Me?“

!["My husband resents me. He won’t admit it because only a 'bad' person would resent their partner for being disabled.... I fear my son is heading there too.... [M]y pain, no longer orphaned.... Because it is mine. It is not something I can share...." Quote from Valerie, "My Pain Made Me Multidimensional"](https://brandeisparentswithdisabilities.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/c5894-valerie-multidimensional.png?w=525&h=263)